In the 80s, my grandmother was living in this building. Mama Aziza. Illiterate. Place Pietri, Sococharbo. Her appartment in Benzerte street has become an art center: Le Cube; and I, an artist. So, begins the story of this film. Parallels. Le Cube. My geometry. My volumes. My sounds.

Excerpt from the film played during the exhibition

At the entrance of the exhibition, five stylish wooden letters take simple geometrical forms: triangle, cube, semicircle. They bring to mind the square or the protractor, especially that their function is not limited to measuring space, but also time. Indeed, the latter has passed by three generations: the first one was illiterate and the last one has written in large letters that everything is alright, literally “no harm“: La bess.

The letters of an unwritten language, a vernacular, are crafted in accordance with these measuring instruments that quantify space. It is about a dialect, darija with words of a rhythm that embraces the instruments of a percussive music. La bess is measured in three beats, that are 3, 5, 6, 7 or 8 beats. All of them release the notes of a score which is written and drawn in codes that artist and composer invented.

The generic formula comprises an ambiguity: interrogative or affirmative, the miniature sculpture La Bess is not punctuated. Is it a question that Myriam El Haïk addresses to the public, or a simple affirmation that concerns one’s state of being: “I am fine?” At first, we notice the signified, as the artist prefers the light spirit of guessing games to the solemn art of calligraphy. The “there is no harm” of daily life, elevated to the rank of a common good, going from mouth to ear and extending to bodily contact, contains recipes for games and multiple creations to share in a friendly atmosphere. In the language of El Haïk, le bess is definitely conjured by the bass of a continuous joy!

A large sculpture made of these four letters is presented in the artist’s studio. It is a composition of signifiers in the form of colored canvasses, mounted on an undercarriage, and which are modulable at will. In short, if “I” is fine, “We” is also fine. When I play, I invent, and thus, we can play, dream, construct, collectively, in a society that prepares us to live together.

Thus, the artist builds a variation of abstract sculptural compositions, with a precarious balance, and names them states. States of grace? Indeed, those who enter the living room, literally La chambre assise (the sitting room) and Bit legless in darija, are pardoned and relaxed. This public space within a private space inspired the installation of Myriam El Haïk, that the artist purged from its traditional charge, to conceive a geometric, modular device, where we can do everything: talk, play, listen and even watch TV, all while following the rules that she has set. In fact, only those rules can establish the intricacies of a savoir-vivre in sound, forms and colors, reminding one that art is the invention of tradition.

Besides, in La Chambre d’assise, we are neither doing the artist’s work nor behaving as public, but we rather, invent forms. The old politeness formulas have given way to wooden modules with which one composes spaces and rhythms; with which we play and we communicate.

In her approach, Myriam El Haïk identifies with the “mother tongue of the poet” that the Franco-German philologist Heinz Wismann defines as the language recreated from “in-between” languages and several other ones. Hence, the range of works on display gives utmost importance to Darija that has been passed from grandmother to granddaughter, despite being confronted with the domination of so many foreign and official languages. Then, it is with the body and the spirit of this playful and multilingual granddaughter that Myriam El Haik tackles the subject of transmission. Through play, the “polyform/politeness formulas” speak of philosophy, aesthetics, morality, religion, social bond, psychoanalysis. “How are you? No harm?” The artist responds by her work that tells the public: “Now is your turn to play!”.

Documentation

• Leaflet of the exhibition

• Map of the exhibition

Press

• “Myriam El Haïk met les formes” by Emmanuelle Outtier in Diptyk n.38

• “Rabat, comment ça va?” in TelQuel n.766

• “Savoir-vivre” in Maison du Maroc n.127

Featured events

“La Bess ?”, “Comment ça va ?”

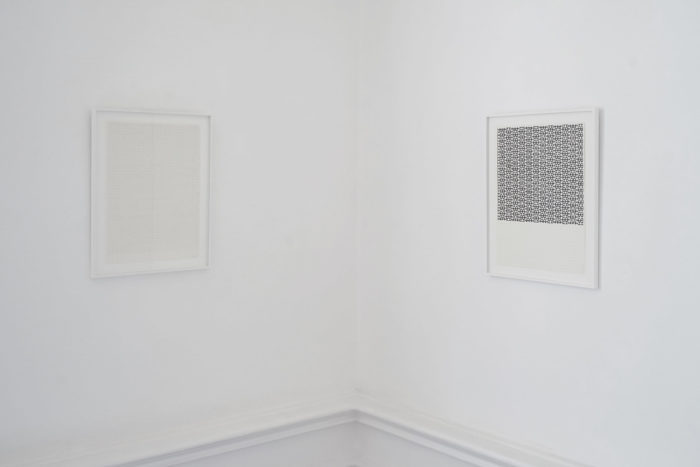

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir.