In 1910 the exhibition “Masterpieces of Mohammedan Art” in Munich presented carpets displayed on walls like paintings, a presentation that made many Europeans visit the Maghreb to study its local crafts traditions.

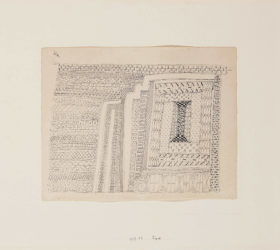

In 1927 – 13 years after his voyage to Tunis – Bauhaus teacher Paul Klee created a drawing based on monochrome “Kilims” made by Tunisian Berbers. While studying its structure and patterns Klee developed a relation between craft object, decorative arts and a specific language of abstraction.

As one of four focal objects of bauhaus imaginista Klee’s drawing Teppich (carpet), one of many attempts by Bauhaus artists to learn from pre-modern design practices triggers a debate around transcultural readings of vernacular objects. Klee’s drawing invites the question from a contemporary perspective, how and through which framings craft objects are transformed into an art work or a design innovation. What is gained and what is concealed in such readings?

According to French-Algerian artist Kader Attia, non-Western museum objects like Berber rugs have been detached from their original meaning by removing them from their initial context. Through a process of abstraction, they have been cleansed from the physical and social body to which they must be connected if they are to function and be complete. To fully understand an object’s identity, Attia argues, we have to reconnect it to the body.

In the context of bauhaus imaginista Kader Attia will produce a new film, based on studis on Berber jewelry that in addition to traditional metals and gems also used coins imported by colonial powers. Through the appropriation of European money, its currency became detached from its original value. The photographs of Berber jewelry from Attia’s new film project unfold a complicit relation between tradition and modernity and point out how intercultural encounters always unleash a never-ending process of exchange and re-appropriation.

It is this open-ended process of transcultural readings that was also foundational for the post-independence art movement in Morocco of the 1960s. It is less know that artists and designers in Casablanca revisited the Bauhaus curriculum by turning to a study of local crafts. Like it is demonstrated in the research undertaken by Maud Houssais, a research wich is also presented in Le Cube, for them, Berber crafts offered an alternative to the existing Beaux-Arts art education, implemented under the French colonial rule. Asserting the need to decolonialize culture and the art school curriculum, artists and intellectuals such as Farid Belkahia, Mohamed Chabâa, Bernt Flint, Toni Maraini and Mohamed Melehi re-visited popular art forms to create a new post-colonial language that aimed to synthesize the arts. This productive friction between different knowledge structures beyond the usual hierarchy of the manual vs the cognitive, the popular vs elite culture is still a challenge for today’s art institutions.

How can the reading of cultures be decolonialized? With the start of bauhaus imaginista’s year program in Morocco in Rabat 23rd/24th of March 2018, this question is reflected through the study of vernacular objects as well as through parallel projects in the 20th century that wanted to go beyond the western paradigms of knowledge production and transfer.

Documentation

• Leaflet, external pages

• Leaflet, inside page

• Poster

• Handout: bauhaus imaginista

• Handout: approach Kader Attia

• Handout: archives captions by Maud Houssais

External link

Website of bauhaus imaginista

Press

• “Le Maghreb se réapproprie le Bauhaus” by Zouina Ait Slimani in Manazir

• “Kader Attia célébre le Bauhaus à Rabat” in Diptyk n.42

• “Kader Attia, le Maroc et le Bauhaus” by Maud Houssais in Diptyk n.43

• “Rabat, lancement de l’exposition Bauhaus Imaginista”, interview with Maud Houssais sur Medi1TV

A visit of the exhibition bauhaus imaginita with Marion von Osten and Maud Houssais

Partenaires

The international exhibition and research program bauhaus imaginista is launched in Morocco on March 23, on the occasion of the centenary of the foundation of the Bauhaus –famous German school of art, design and architecture. With Kader Attia (Franco-Algerian artist living in Berlin), a roundtable, an exhibition and a workshop will explore the connections and cultural transfers between the German Bauhaus movement and the traditional and modern artists and artisans of art in North Africa. This event inaugurates the bauhaus imaginista cycle, an international research program, of exhibitions and events dedicated to the reception of the Bauhaus in the world, during the 20th century.

bauhaus imaginista is made possible by funds from the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media. The German Federal Cultural Foundation is supporting the exhibition in Berlin and the German Foreign Office the stations abroad. Media partners are 3sat and Deutschlandfunk Kultur.

Partners abroad are the Goethe-Instituts in China, New Delhi, Lagos, Moscow, New York, Rabat, São Paulo, and Tokyo. bauhaus imaginista is realized in collaboration with the China Design Museum / China Academy of Arts (Hangzhou), the Independent Administrative Institution of National Museum of Art / The National Museum of Modern Art Kyoto, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art (Moscow), SESC São Paulo and Le Cube – independent art room.

curators zone

bauhaus imaginista

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.

Photographies par Abdessamad El Montassir et Stephanos Mangriotis.